Pandemic Pedagogies – Learning from the Black Death and 1918 Influenza Pandemics

By a chance of fate, I found myself teaching a Religious Studies course on the End of the World this spring at CSU Chico, just in time to watch the world slide headlong into the coronavirus pandemic. Needless to say, the backdrop of a global pandemic has added a more serious edge to conversations with my students about the end of the world, which is hardly a light topic to begin with. As we moved from zombies and killer robots to histories of the Biblical apocalypse and dystopian futures, the many differently imagined end times scenarios increasingly felt contrived next to the very real disaster that was unfolding all around us.

While not an apocalypse of Biblical proportion, this current pandemic has forced everyone to experience what it means to suddenly have your social world disrupted in some form, ranging from minor to extreme. And true to its name, the coronavirus apocalypse has revealed important insights about the state of our world (both welcome and painful). And in a somewhat unexpected but perfectly apocalyptic twist, the sudden emergence of forgotten blue skies and previously absent other than humans in our world has made visible what was previously hidden. And by revealing aspects of our world that we have forgotten (or for some have never been seen before), it is a powerful reminder of why the language of the apocalypse continues to hold such imaginative power.

In trying to help my own students make sense of this shifting landscape, and based on feedback from them, I revised the final weeks of our class to take a step back from our focus on the apocalypse and delve into some historical perspectives from past pandemics and fears about the end of the world. Like earlier moments of contagion that threatened the body politick–from the Plague of Justinian and the Black Death to more recent cases of Influenza, HIV, and Ebola–understanding these past outbreaks can provide insights into our own experiences.

Given the short period of time, I choose two key moments to focus on–the Bubonic Plague of the mid-1300s and the 1918 Influenza outbreak–since they offer points of commonality and contrasts in the scope of their impacts (catastrophic versus severe), the mechanism of how they spread (bacterial versus viral), and how people reacted to them. In working on putting class materials together it immediately became apparent there was a lot of interest in how to use the coronavirus as a teachable moment, particularly to help students think about the ways a global pandemic draws out long-standing social and political inequities and fears.

As many of my students noted in our online discussions, there are more than a few important parallels with the 1918 outbreak and what is happening in 2020. From religious to political responses to the Black Death and the outbreak of Influenza in 1918, there are some powerful lessons we can draw from these historical moments.

Two examples are worth highlighting here, one from each of the periods in question.

Medieval flagellants as seen during the period of the Black Death.

Black Death: Party, Help, Flee, or Repent?

As the Plague swept through Europe starting around 1347, and as more and more people began to die, social fabric began to unravel across Europe. If there is a chance you will be dead tomorrow, what do you do? Do you go out and dance and drink and celebrate with anyone you know who is still alive, cursing the gods for your fate? Or do you volunteer to help the sick and dying, and likely end up dead yourself? Do you flee to areas that may be safer (which really did not work in the 14th century case)? Or do you turn to God and join the flagellants movement, turning your religious piety into a public spectacle in the hopes of averting a worse fate?

All of these were possible social responses to the horrors of the times. When I asked my own students how they would respond if they found themselves magically transported back to this period, their own responses covered the same range of responses, with the exception of joining the flagellants movements.

We are seeing many of the same sorts of responses today to the coronavirus pandemic (minus the Flagellants Movements so far) as people try to make sense of and react to the uncertainties of the day.

The other relevant example (two examples actually) from the period of the 1918 Influenza outbreak are in some ways even more instructive for what we are going through today in 2020, both in their political echoes and in the ways the public and politicians responded to the outbreak in the US.

Influenza 1918: Denying the Truth & Fighting Masks

Following a brief lull in the summer of 1918 after the first wave, the second wave of Influenza came back with a vengeance in the fall of 1918 in what would turn out to be the worst pandemic in modern history, topped only by the Black Death in its sheer destructive impact. But what resonates with our current moment are two specific events. The first was the September 28, 1918 Liberty Loan parade in Philadelphia. The second was the formation of the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco sometime in the late fall of 1918.

Ad for the 4th Liberty Loans drive.

Despite warnings from various public health officials and doctors (which were being officially censored at this time with the full support of Congress and President Wilson thanks to the newly passed Sedition Act), the political leaders of Philly decided that, hell or high water, the show must go on. It’s important to recall that the parade was meant to help sell the Liberty Loans, which were being used to fund WWI. The Fourth Liberty Loans bond drive was set to begin on the 28th, so to cancel the promotional parade in Philly would have been a patriotic blow to the war.

However, an outbreak which appears to have begun at the shipyards (where a large number of workers had been brought in to work on constructing ships for the war) was already beginning to spread to the city, and the parade, which brought in an estimated 200,000 people, sent the Influenza outbreak into overdrive mode. Within a few days of the parade, Philly saw a massive spike of outbreaks and deaths, all directly linked to the parade and throngs of people crammed shoulder to shoulder in attendance.

The hard lesson Philly learned that day was that you can hide the truth, but you cannot hide a virus. Even today public officials point to this incident in Philly as an example of what not to do in a pandemic.

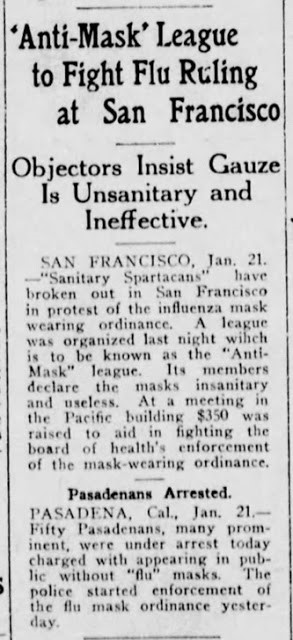

News clipping from LA Herald, Jan 21, 1919.

The other instructive example is the anti-mask movement in San Francisco, which as I noted earlier, appeared in response to a mandatory mask ordinance which the city put into place on October 24, 1918. What began as a public health suggestion in September quickly turned into a mandatory ordinance after much of the public refused to follow what today we call “social distancing” guidelines and the number of reported cases continued to increase. But soon public resistance–including at least one reported shooting and hundreds of arrests for failure to wear masks in public–led then mayor James Rolph to rescind the mask ordinance on November 21, less than a month after it went into effect.

Predictably, there was a surge in outbreaks soon after these social distancing measures were eased. Along with the end of the mask ordinance, schools and other places of business soon resumed operation as well. This led health officials to reinstate the mask ordinance in mid-January as the rate of infections and deaths continued to increase, producing an even stronger public reaction, and this is where the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco becomes a timely example of learning from our past.

An example of this anti-mask coverage from the LA Herald just a few days before a large public gathering is instructive, referring to those involved as “Sanitary Spartacans” and noting the formation of a new “Anti-Mask” league. Also notable is the mention of ongoing arrests in Pasadena, signaling this was not an isolated SF phenomenon.

A huge public gathering on January 25, 1919 at the Dreamland Rick, reported to have nearly 4,500 people in attendance, formalized a petition to the city (delivered a few days later to the Board of Supervisors) to remove the mask ban, citing everything from infringement of civil rights and economic harms to conspiracies about forced government vaccinations and political tyranny! Sound familiar? The movement, which included many local elites and civic leaders, was successful. The city rescinded the mask order a few days later on Feb 1, 1919. The death rate (influenza & pneumonia together) was quite serious, registering at 673 per 100,000 people (~500,000 people living in SF in 1918). In total, San Francisco had at least 45,000 recorded cases of Influenza and more than 3,000 deaths in the period between 1918 and 1920, making it one of the hardest hit of US cities.

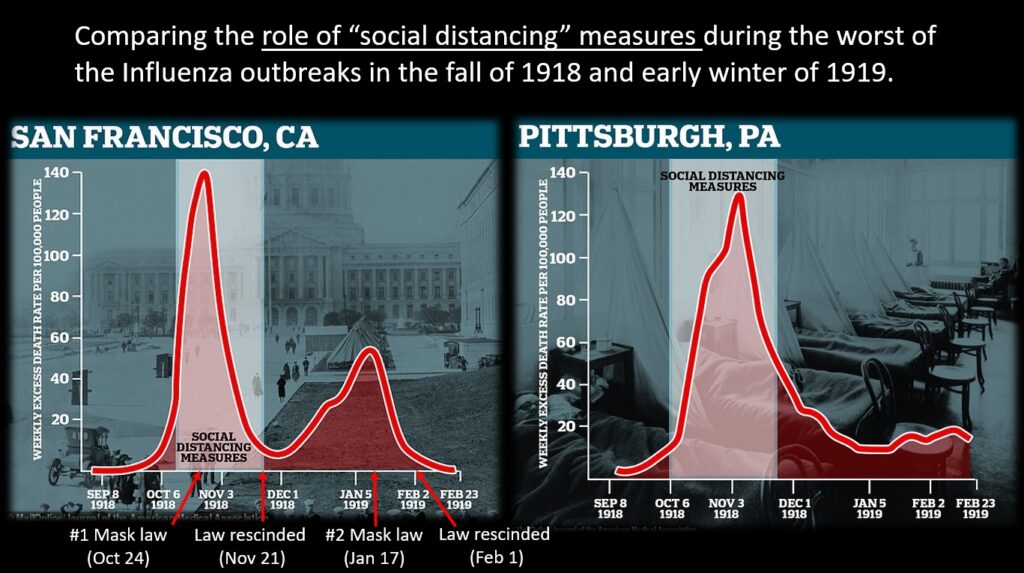

As you can see from the image below, which I put together for my class lecture, the adoption and then abandonment of the mask ordinance can clearly be seen in the outbreak levels, although scholars have been cautious to directly correlate the mask ban as the cause. As we often say in academia, correlation is not causation, but it is hard not to see how one leads directly to the other in this case. NPR Washington Investigative Correspondent Tim Mak has also written (tweeted to be precise) about this in some detail for anyone interested, and just recently did a piece you can listen to on Spotify here.

Comparing Social Distancing Measures in 1918.

But what is more certain is that social distancing measures do make a difference, and existing research backs up that assertion, while noting scientists need more empirical data to be able to say what measures work better and why based on the context. As we have seen in recent weeks, protests against social distancing in states ranging from Ohio to Michigan and California to Wisconsin are on the rise. However, unlike in the case of San Francisco, President Wilson wasn’t making public declarations in support of anti-mask protestors and encouraging people to resist social distancing and public quarantine health measures in the name of freedom or whatever nonsense those opposed to sensible public health precautions are claiming.

In each of those earlier cases we can learn a lot from historical precedents if we are willing to look with a critical eye, something that not everyone is always willing to do. But the historical lessons are there, nonetheless. For educators trying to help students gain some perspective on our current pandemic, these can be great lessons to draw from.

I have put some links to my teaching resources for these two sections below for anyone interested, including copies of the two video lectures I recorded for my students.

With most everyone in education isolated at home once schools closed down, a huge spike in online pedagogy began to spread, and some of it has been focused on how to teach about the current pandemic. One noteworthy example is the #coronavirussyllabus project, which is a “crowdsourced cross-disciplinary resource” compiled with numerous resources for teaching about the coronavirus and other pandemics. It began as a social experiment after a series of social media posts by Brown University biology professor Anne Fausto-Sterling and Social Science Research Council President Alondra Nelson but has grown and morphed since then. The project was even highlighted in a recent article by Time Magazine exploring how universities in the US are responding to coronavirus.

On March 11 Fausto-Sterling tweeted:

“I’ve been thinking about the virtual classroom. It seems like a perfect moment to scrap the existing syllabus and teach the moment. No matter the course topic, I can see how plagues, pandemics, and health care could become the meat of the lesson. #teachthevirus.”

A second shared coronavirus teaching resource worth looking into is being curated by TLA, the Teaching and Learning Anthropology Journal, called Teaching COVID-19: An Anthropology Syllabus Project. There are a number of other great resources that have emerged in the past few months covering a wider range of topics now found under the #teachthevirus and #coronavirussyllabus hashtags. And in my own circle of religious studies and political ecology peers a recent call for papers went out on the theme of ‘Religion and the Coronavirus Pandemic’ from the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature, and Culture (JSRNC).

I also ran into an exciting project put together by Canadian history teacher Katy Whitfield called “Stories from Self-Isolation” thanks to the pedagogical cross-connections that have been happening between educators on Twitter. Katy is collecting stories from Canada and elsewhere about people’s experiences during the pandemic, and she already had over 200 stories as of the end of April. Everyone is encouraged to contribute something to her story project.

Whitfield also did an excellent video interview with Dr. Samantha Cutrara for the series Imagining a New We, which looks at ways people are transforming the Canadian history classroom. For anyone teaching social issues and history, this interview has a lot of great ideas to draw from, so I highly recommend checking it out. And this is part of a bigger Pandemic Pedagogy video series also worth checking out.

One day we may look back on this as not just a teachable moment, but as a defining moment in our teaching.

The Black Death & 1918 Influenza Pandemics

As I noted earlier, here are some resources to consider using if you want to teach about these two earlier periods in relation to what is going on now with the novel coronavirus. I spent a week on each section, with one lecture and class discussions around the materials listed below, but these could certainly be expanded and added to for a longer section or multiple class sessions.

Bubonic Plague / Black Death

Readings:

- “The Black Death – The Greatest Catastrophe Ever” Ole Benedictow

- “Visualizing the History of Pandemics” Nicholas LePan

- “Religious Responses to the Black Death” Joshua Mark

- “Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present – Plague as a Disease (Excerpt)” Frank Snowden

Video:

- “Disease” Crash Course World History” [Watch video online]

- “How You Could Have Survived the Black Death” [Watch video online]

- “Europe on the Brink of the Black Death” [Watch video online]

1918 Influenza Pandemic

Readings:

- “1918 Pandemic Influenza Historic Timeline” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America” John Barry, Smithsonian Magazine

- “What New York Looked Like During the 1918 Flu Pandemic” New York Times

- “The Forgotten Epidemic: A Century Ago, DC Lost Nearly 3,000 Residents to Influenza” Washingtonian

- “How DC Churches Responded When the Government Banned Public Gatherings During the Spanish Flu of 1918” Caleb Morell

- “Some Reflections Growing out of the Recent Epidemic of Influenza in Washington DC – Nov 3, 1918” Rev. Francis J. Grimke

- “A Pandemic Billy Sunday Could Not Shut Down” John Fea, Religion News Network

Videos:

- “Influenza, 1918″ PBS American Experience [Watch video online]

- “History Of The 1918 Flu Pandemic In 7 Minutes” BuzzFeed News [Watch video online]

- “Spanish Flu: A Warning from History” Cambridge University [Watch video online]

- “How the Coronavirus Pandemic Compares to the Spanish Flu” New Yorker [Watch video online]

I’ve also put additional resources I used to compile these lectures into a shared Pandemic Pedagogies web folder you can access here. For anyone that might want to use this material in their own classes, here are the two powerpoints I created and which are recorded in the lectures below (minus my class details).

- Black Death Lecture (.pptx)

- 1918 Influenza Lecture (.pptx)

Here are the two video lectures I recorded for my class as well, for anyone who might be interested. These are both based on the powerpoint above. (*Note: I accidentally referred to the Black Death as the ‘Black Plague’ in two spots-ugh I know, I know. But it wasn’t worth re-recording the entire lecture just to fix this. It has been updated in the powerpoint above though).

**Updated (11/1/2020)

Since I originally posted this I have continued to develop these materials, and also did another lecture on pandemics, all of which you can find on my End of the World podcast below. The two bonus episodes use the original audio from the recorded lectures above, with some minor editing, so you can either watch the video or listen to the podcast.

The End of the World Podcast

Episode 11 – Disease and Pandemic

Episode 11 Bonus (Part 1) – Black Death

Episode 11 Bonus (Part 2) – 1918 Influenza