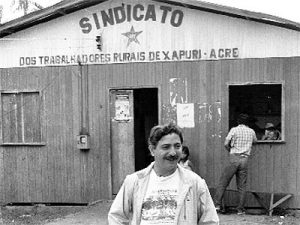

The Second Murder of Chico Mendes

The following is a copy of an article written in 1990 by Osmarino Amancio Rodrigues (successor to Mendes in the CUT–rubber tappers union) as a response to media and publicity following the assassination of Chico Mendes, a Brazilian union activist and defender of the Amazon. Mendes was assassinated by capitalist thugs working for local ranchers and loggers at his home on December 22, 1988. In the course of doing some unrelated research that involved reference to Mendes and this article by Rodrigues, I kept running into dead links or references to the article, but no actual copies of the article. After several hours of dedicated internet digging I finally came across a link I could backtrace through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. For the sake of other scholars and activists who might also need this article, and in honor of his memory, it is reproduced here in its entirety as found on the original site, the Amanaka’a Amazon Network, which no longer exists except as a digital ghost.

The following is a copy of an article written in 1990 by Osmarino Amancio Rodrigues (successor to Mendes in the CUT–rubber tappers union) as a response to media and publicity following the assassination of Chico Mendes, a Brazilian union activist and defender of the Amazon. Mendes was assassinated by capitalist thugs working for local ranchers and loggers at his home on December 22, 1988. In the course of doing some unrelated research that involved reference to Mendes and this article by Rodrigues, I kept running into dead links or references to the article, but no actual copies of the article. After several hours of dedicated internet digging I finally came across a link I could backtrace through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. For the sake of other scholars and activists who might also need this article, and in honor of his memory, it is reproduced here in its entirety as found on the original site, the Amanaka’a Amazon Network, which no longer exists except as a digital ghost.

The Second Murder of Chico Mendes

By Osmarino Amâncio Rodrigues

F r i e n d s :

Building this road has not been easy. In addition to the violence of killings and deforestation in Brazil, we have had to overcome many problems. Under the leadership of Chico Mendes we learned, little by little, to join forces, to cut down not trees but prejudices. From the union struggle, from the struggle for Agrarian Reform, we learned that the indigenous peoples are our friends. The Alliance of the Peoples of the Forest is a fact today.

But we did not stop there. We began to understand that our struggle was in the interest not only of ourselves, but of all Brazilians. And even more, of all the world. Although ecology was at first a strange word to us, it was gradually assimilated as we realized that our practice had long ago incorporated its concerns.

Extractive Reserves are our own proposal for land reform adapted for Amazonia, and… they are inseparable from real land reform [in Brazil] as a whole.

We knew how to move from the local union struggle to a regional level, creating the National Council of Rubber Tappers and the Alliance of the Peoples of the Forest. On the national level, we sought to consolidate our relations with the rest of the Brazilian workers through the Worker’s Central Union – CUT – which was the first national organization to incorporate the proposal of Extractive Reserves on its agenda of political struggles.

Today there are still those who have not understood that the Extractive Reserves are our own proposal for land reform adapted for Amazonia, and that they are inseparable from real land reform in Brazil as a whole. It is necessary to limit migration to Amazonia, and for this reason it is an illusion to believe that the demarcation of Extractive Reserves, without a real democratization of access to land in Brazil, can be an alternative for our region.

We say this not only from our point of view as inhabitants of Amazonia. Access to land in the rural workers own regions is justified as much from a social viewpoint as from an ecological. There they know the land, the rivers, the plants and the-animals. There they develop a culture together with their relatives and neighbors. This needs to be taken into account when one discusses land reform in Brazil. And this leads us to a natural unity with the landless, with those displaced by [hydro-electric] dams. our practice has tied us with the movements that fight for land and social justice, and these movements have also began to understand the importance of the environmental question.

Today many people say they are environmentalists and speak of Chico Mender without having Chico’s wider vision, which did not separate the social struggle from the ecological struggle. It is as if they committed a second assassination of Chico.

We realized that, despite advances obtained by social movements in Brazil, the authorities’ disregard for our needs and demands has remained great. We began to look outside for allies, principally among the European and North American ecologists. Through them we got as far as the World Bank, where we denounced what had been done in Brazil with loans obtained in the name of environmental preservation and demarcation of indigenous lands, as was the case of BR364 highway, from Cuiaba to Porto Velho. We were able to unmask the authorities for the world to see.

The costs of this struggle have been high. Ten years ago we lost our companheiro Wilson Pinheiro, the creator of the “empates” in~l976. Since then many others have fallen: Ivair Higino, Jesus Matias, Fontelles, Josimo, Chico Mendes, and recently our companheiro Canuto, in Para. The name of Chico Mendes has been raised so high that it seems he did not belong to this world, where we continue to live in the same manner as he lived, suffered, struggled and died.

Today I see that ecology occupies a large space in our press but in a way that is very distant to us. I still remember Chico telling of a reporter from the O Estado de Sao Paulo newspaper who walked out of a conference because Chico spoke of land problems and of threats against his life. This was not ecology but union struggle. Since they say so often that Chico was an ecologist, why was he the first ecologist killed in Brazil?

Today many people say they are environmentalists and speak of Chico Mendes without having Chico’s wider vision, which did not separate social struggle from ecological struggle. It is as if they committed a second assassination on Chico. Not long ago some environmental organizations rejected the participation of CUT in forums of debate about the environmental question. They didn’t know – or didn’t want to know, that CUT was the first national political organization to raise the banner of Extractive Reserves, and one in which Chico was a leader.

We don’t want to break the alliance between those who fight for social justice and those who fight for ecology. We, Rubber Tappers, have become environmentalists without ceasing to be unionist and to fight… for Agrarian reform [in Brazil].

Chico had the great quality of being able to join things together, to overcome prejudices. We honor the commitment that Chico left us. We don’t want an empty environmentalism that speaks of nature while forgetting man; that speaks of the defense of the Forest while forgetting the Peoples of the Forest. This is our contribution to the world environmental movement: defense of nature and social justice are inseparable.

We, Rubber Tappers, have become environmentalists without ceasing to be unionists, to fight for land and Agrarian Reform together with Indians and other Brazilians. We should seek international alliances while never ceasing to strengthen our local alliance’s here in Brazil against this unjust and devastating mode of development.

Sometimes we have neglected our internal bonds, attracted by offers of material help. But without political clarity, the dollars and the foreign help will be of no use. For example, we need to prove the viability of Extractive Reserves as a development alternative for Amazonia. But can the Extractive Reserves be an island of progress surrounded by misery and injustice on all sides?

We want to strengthen our alliance with environmentalists without losing our own characteristics as workers who want a a society based on ecology, where we can live with dignity, social justice, and enjoyment of all the good that knowledge, science and technology can bring us.

Copyright – Osmarino/Amanaka’a Amazon Network