“You Didn’t Build That” – Perpetuating the Myth of American Exceptionalism

Andrew Cline had a recent article in The Atlantic where he attacks Obama for a recent campaign speech where Obama made the following remark: “If you’ve got a business — you didn’t build that.” The article, called What ‘You Didn’t Build That’ Really Means—and Why Romney Can’t Explain It, claims to offer a critique of Obama’s comments as well as a political analysis of what a savvy Romney campaign should have done in response. The problems with Cline’s piece, and there are many, can be summed up with one simple phrase–historical ignorance fueled by blind American patriotism. Cline, who is editorial editor at the New Hampshire Union Leader, is no Obama fan to begin with, but it is his argument, rather than his party politics, that really stinks. But for some reason this piece, which has drawn a lively response on The Atlantic‘s web site, seems to stand out as unusually bad even for the Atlantic audience. As one particularly incensed commentator remarked in response to the article: “I’ve just decided to never, ever renew my subscription to the Atlantic.” “The writer of this article should be ashamed for pandering to pathetic propagandizing,” fumed another reader.

The heart of Cline’s argument is the following tag line to his article: It’s only a four-word phrase, but to conservatives, it means so much more. The problem of course is that the “conservative” reading of American history that underlies Cline’s argument is nonsense at best, and outright historical fabrication at worst. To help show the faulty logic in this piece, let’s consider a few examples.

Error #1: “A philosophical rewriting of the American story”

Cline’s central argument int his piece, that Obama’s statement was akin to turning founding father and current right-wing beau Thomas Jefferson on his head.

On behalf of all Americans, the Declaration of Independence asserts, in Thomas Jefferson’s words:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. –That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…

Jefferson, whom Democrats claim as the progenitor of their party and whom they celebrate with annual “Jefferson-Jackson Dinners,” was perfectly clear. The people of the United States created the government for one purpose only: to secure their rights. That is, the people, their possessions and their God-given rights existed prior to the state, which the people created to serve them.

The problem with this logic is the leap from the Declaration as an ideological statement to the actual reality of politics which underlie it. When Jefferson and others wrote these words, it was to affirm rhetorically what would be enshrined nearly a decade later in the Constitution, namely that individual rights have no foundation for their expression or protection without a legal framework to secure them. Notice the need to explicitly state that point by the drafters, including Jefferson: “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted…” Without something to back up these claims–in this case a government–all that fluffy talk of “self-evident truths” and “equality” is meaningless, as any Native American or enslaved African could have easily noted.

It was precisely this reliance on the whims of a divine sovereign that had led to American colonization to begin with–another example of Cline’s historical Amnesia. So in fact Cline’s argument about Jefferson’s intent in the Declaration is itself a “philosophical rewriting of the American story,” and a rather ironic one at that. His claim that “the people, their possessions and their God-given rights existed prior to the state, which the people created to serve them” cleverly ignores the fact that it took the Constitution, a secular legal document only possible once there was a state framework to enforce it, before these philosophic ideals could come into political reality. Perhaps someone should remind Cline that the DoI was adopted by the 13 States at the Continental Congress of July 4, 1776. That’s right, it was 13 governments agreeing to disagree with another government body–the British crown. This was not some religious declaration by an autonomous public devoid of any governmental structure or influence, contrary to what Cline’s historical whitewash would have us believe. He would have done well to read all the way to the end of the DoI, where it clearly states the point of the Declaration:

It was precisely this reliance on the whims of a divine sovereign that had led to American colonization to begin with–another example of Cline’s historical Amnesia. So in fact Cline’s argument about Jefferson’s intent in the Declaration is itself a “philosophical rewriting of the American story,” and a rather ironic one at that. His claim that “the people, their possessions and their God-given rights existed prior to the state, which the people created to serve them” cleverly ignores the fact that it took the Constitution, a secular legal document only possible once there was a state framework to enforce it, before these philosophic ideals could come into political reality. Perhaps someone should remind Cline that the DoI was adopted by the 13 States at the Continental Congress of July 4, 1776. That’s right, it was 13 governments agreeing to disagree with another government body–the British crown. This was not some religious declaration by an autonomous public devoid of any governmental structure or influence, contrary to what Cline’s historical whitewash would have us believe. He would have done well to read all the way to the end of the DoI, where it clearly states the point of the Declaration:

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare…that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do.

Notice the emphasis on the power of states–not people–as the concluding emphasis. It affirms the rights of states–not individual people–to declare war and peace, make alliances, and create the atmosphere which can support commerce, not the other way around. Such an argument is simply conservative historical nonsense. We could also problematic claim that Jefferson, Washington and others were Christians, when in fact many of them were Deists, further complicating his Cline’s quasi-religious argument, but that is for a different debate.

Error #2: The Magic Colonial Middle Class

Cline’s second major problem is again a historical one, and once again is a historical fabrication. He writes:

“That’s how we created the middle class,” he [Obama] said. “We created.” Collectively.

Except that is entirely wrong. American individuals created the first American middle class while subjects of King George III.

“In the early stages of a colony’s settlement, rapid upward mobility was very common,” historian Edwin Perkins wrote in The Economy of Colonial America. “Land was initially easy to acquire, and many families which started with little capital became relatively wealthy after two or three generations. Many indentured servants, who served out terms of 4 to 7 years of quasi-slavery, went on to become tenant farmers, later bought land, and eventually accumulated sizable wealth, sometimes joining the colonial elite.”

The “system” did not create America’s middle class. The free middle class rebelled against the king to create the system, and their own wealth. Does Obama think that John Hancock, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison and John Adams owed their wealth to the British government? Does he think King George “allowed” them to prosper?

For starters, it is astounding to read someone claiming there was an American middle class in the colonies, or that there was somehow a large and upward movement of the entire colonial public at this time. Yes, there was an improving standard by immigrant European standards, but that is not the same thing as general social mobility. But this should come as no surprise, given that he cites Perkins as his historical source. Edwin Perkins is known for denying that economic inequality was growing worse by the end of the 1700’s in America and claiming that economics were not an underlying cause of the American Revolution–both assertions that are hard to defend given the actual economic realities of early colonial America. As one review of his book notes: “In his assertion of colonial America’s high standard of living, the author chooses to neglect the existence of poverty and the beginnings of public and private assistance for the destitute.”

But setting aside this questionable historical validity for a moment, the central problem remains that to speak of a middle class in American during the 1700s, and then to somehow suggest that “John Hancock, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison and John Adams” were somehow a part of the American middle class at that time, and that they did not have wealth directly related to the British is quite astounding. There is no possible historical argument I can think of which could ever make Jefferson or Franklin into middle class citizens by any colonial standard. These were the cream of the revolutionary colonial elite, the equivalent to the colonial 1%. We would do well to recall that many of the founders had large plantations full of enslaved Africans, and were involved in the triangle trade of rum, sugar and slaves–hardly an area dominated by Cline’s mythic colonial middle class. Lest we forget, take a look at this chart from Encyclopedia Britannica.

| slaveholders | non-slaveholders | ||

| Founding Father | state | Founding Father | state |

| Charles Carroll | Maryland | John Adams | Massachusetts |

| Samuel Chase | Maryland | Samuel Adams | Massachusetts |

| Benjamin Franklin | Pennsylvania | Oliver Ellsworth | Connecticut |

| Button Gwinnett | Georgia | Alexander Hamilton | New York |

| John Hancock | Massachusetts | Robert Treat Paine | Massachusetts |

| Patrick Henry | Virginia | Thomas Paine | Pennsylvania |

| John Jay | New York | Roger Sherman | Connecticut |

| Thomas Jefferson | Virginia | ||

| Richard Henry Lee | Virginia | ||

| James Madison | Virginia | ||

| Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | South Carolina | ||

| Benjamin Rush | Pennsylvania | ||

| Edward Rutledge | South Carolina | ||

| George Washington | Virginia | ||

Error #3: The Myth of American Exceptionalism

Cline’s final argument once again rests on the false claim that this country was build by the sweat and toil of so many hard-working American businessmen, all working out of sheer good will and capitalist disinterest. This classical conservative myth is further perpetuated by a clever slight of hand in the first paragraph below. Can you spot the rouse that Cline attempts in order to criticize Obama?

Obama’s one nugget of a point — that infrastructure facilitates commerce — is disputed by no one. Nor does any serious person dispute that everyone should pay for that infrastructure or for the essential services the people have tasked the government with providing. It is a fundamentally American principle.

“Every man is under the natural duty of contributing to the necessities of the society; and this is all the laws should enforce on him,” Jefferson wrote to F.W. Gilmer in 1816.

What had always separated our “system,” to use the president’s word, from other systems was not that we had fire departments and teachers and roads and bridges. Europe has much grander examples of all of those. What we had, and others did not, was a tight constraint on the scope of government action and a population that is extraordinarily industrious and entrepreneurial.

Once again we see the power of conservative historical whitewashing in action. “Nor does any serious person dispute that everyone should pay for that infrastructure or for the essential services the people have tasked the government with providing. It is a fundamentally American principle.”

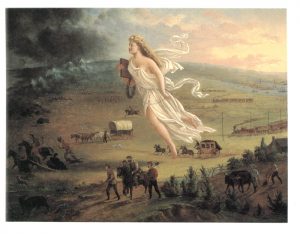

Not only is this not a “fundamentally American principle,” it is not an American principle at all, only an American myth. All of the major industrial developments that led to the rise of American prior to WWII, the survival of early colonists, the expansion Westward, the agricultural economy of the South, the railroad expansion into Great Plains and eventually the West Coast, and the slow but steady frontier settlement between the coasts, was all fueled by stolen land and slave labor. Americans did not pay for this infrastructure, they forced slaves and Natives to give it up for virtually or actually nothing in exchange, except the price of their lives. This is the most crass form of white supremacy and racism, and should be enough by itself to disgust any half-intelligent person, much less the supposedly sophisticated readers of The Atlantic.

“What we had, and others did not, was a tight constraint on the scope of government action and a population that is extraordinarily industrious and entrepreneurial.”

No. Actually what America had was a legacy of genocide, slavery and stolen land in the name of Anglo-Saxon civilization and Christianity, happily enforced and expanded by the American government in the name of “industry” and “commerce.” Now that is “a fundamentally American principle” if there ever was one!

Until next time…learn your own history, it might actually matter some day.

###

They were put in that order purposely. They are in the order of importance.You can’t have liberty or pursuit of happiness without life. That pretty much goes without saying. You can’t pursue happiness with liberty. If you have no liberty, whatever happiness you have is given you by those who have restricted your liberty. So now go into the reverse order. Can you have life without liberty and the pursuit of happiness? Sure, lots of people do. Can you have liberty without the pursuit of happiness? Sure. Many people have liberty but don’t pursue happiness. But that is their doing, not ours. In short, Jefferson put these three ideals in the order they need to be in. To have all three, first you must be alive, then you must have liberty. When you have the first two, then it is up to you to pursue happiness. Note, Jefferson wrote PURSUIT of happiness, not that you have a right to happiness. It is up to us to pursue. Many people feel they are owed happiness. They are not correct and tend to spoil it for the rest of us, as they expect us to give them what they think they need in order to be happy. The pursuit implies working toward your happiness, not trying to convince others to do the work for you.