Northern Snows, Southern Fires

Here in northern Ohio we had the first short snowfall recently, leaving a thin blanket of snow on the ground and between the tree branches. I associate a certain sense of calm with the first snowfall–even as I morn the gradual vanishing of the fall colors and crisp evening nights.

Yet as I read the daily news headlines and slowly read through the various email lists I am on, it’s impossible to escape the storm of social protests and political fires erupting across much of South America rights now–from protests in Chile and Ecuador to the massive unrest in Bolivia as the (now apparently former) President Evo Morales fled to Mexico amidst the growing social unrest, unrest by all accounts that has wide-ranging roots: in the political left, right, and center; among both urban and rural; and especially from the youth.

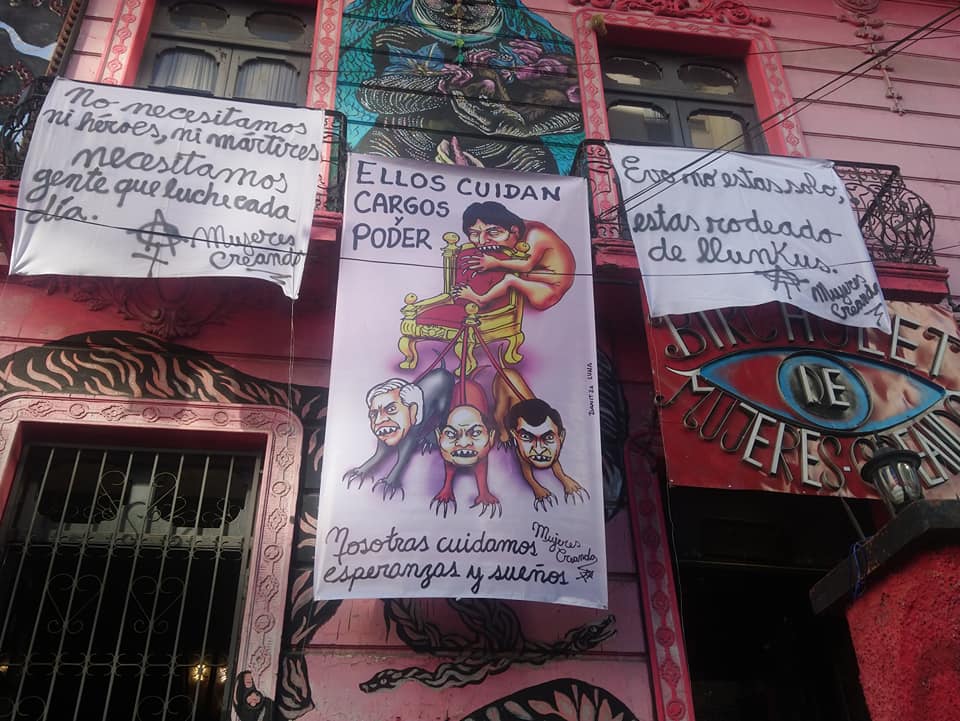

Banners in front of the Mujeres Creando space. The main banner reads: “They (men) care for rank and power, we (women) care for hope and dreams.” (Photo credit: Mujeres Creando)

Added to all of this is the complex geopolitics swirling around Bolivia, from US neoliberal foreign policy goals to Chinese and European interest in natural resources–in particular lithium. Because I’ve had an interest in Andean politics as part of my earlier PhD research I have been trying to stay abreast on what is going on, but the political dynamics are such that it makes it really complicated to really understand events on the ground without being on the ground.

Having said that, there have been some really good critques in the past week about what is going on from a local or regional perspective. I found four articles in particular helpful for making sense of events on the ground, and I’ve listed each with a few highlighted excerpts. The first three offer local and regional perspectives and critiques, while the last looks more at global resource politics, in particular the issue of multinationals and extractivist politics with lithium.

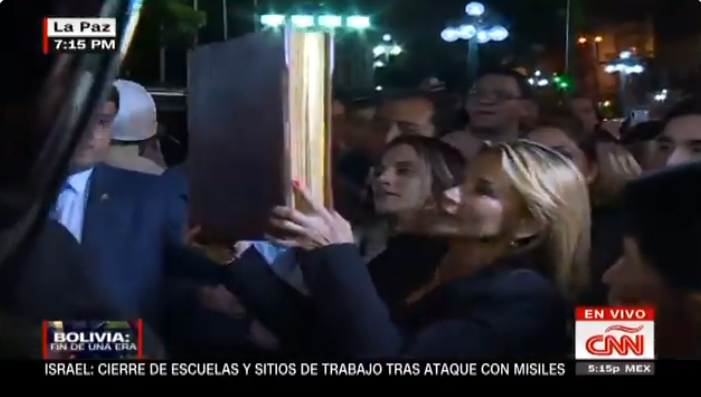

It’s also troubling to note that in the past 24 hours (on Nov 12) Deputy Senate Speaker Jeanine Áñez paraded into the Quemado Palace in La Paz with a leather bound bible after illegally proclaiming herself the country’s new interim president. “The Bible returns to the Palace,” Áñez declared. She has already made it clear from past comments that besides her right-wing leanings, she is also hostile to Indigenous cosmopolitics, as seen in the following tweet:

I dream of a Bolivia free of satanic indigenous rituals, the city is not for the Indians, they should go away to the highlands or the plains!

Self-declared interim president Jeanine Áñez parading into the palace with a large leather-bound bible. (Photo credit: CNN)

The move of declaring herself interim President without a legal quorum of representatives in the legislature further confirms she has no regard for democratic politics, and does not seem to bode well for the future of democratic politics in Bolivia.

So if you’re in a hurry and don’t want to read a lot of dense analysis, here are some samples that may help give a bit of a picture of what is going on. But it is important to keep in mind that the situation changes daily–if not hourly–but these posts do provide some good basic context.

4 Critical Analysis on Bolivia

1. Bolivia: The Extreme Right Takes Advantage of a Popular Uprising

by Raúl Zibechi (Nov 11, 2019) | leer en español aqui

What caused the fall of the government of Evo Morales in Bolivia is an uprising by the people of Bolivia and their organizations. Their movements demanded his resignation before the army and police did. The Organization of American States sustained the government until the bitter end.

The context for what is taking place in Bolivia didn’t start with electoral fraud, rather it began with systematic attacks by the government of Evo Morales and Álvaro García Linera against the same popular movements that brought them to power, to the point that when they needed the movements to defend them, the movements were deactivated and demoralized…

This sad outcome has precedents that go back, in a short version, to the march in defense of the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS) in 2011. After that massive action, the government began to divide the organizations that convened the march…

For the majority of people in Bolivia, the elections of October 20 were fraudulent. The first counts indicated there would be a run-off election. But the counts stopped without explanation and the results presented the next day showed that Evo had won the first round, obtaining just a 10% lead over his next rival, though without receiving over 50% of the vote…

The immense majority of people who live in Bolivia refused to enter into the game of war that Morales and Garcia Linera set up when they resigned and sent party members to participate in destruction and looting (especially in La Paz and El Alto), probably so as to force military intervention and justify their claim of a “coup” which never existed. The majority of Bolivians have also stayed out of the game played by the extreme right, which acts in violent and racist ways towards popular sectors.

If there is anything left of ethics and dignity in the Latin American left, we should be reflecting on power, and the abuses committed in its exercise. As feminists and Indigenous people have taught us, power is always oppressive, colonial and patriarchal. That is why they reject leaders (caudillos), and why communities rotate their leaders so that they don’t accumulate power.

We cannot forget that in this moment there is a serious danger that the racist, colonial and patriarchal right manages to take advantage of this situation to impose rule and provoke a bloodbath. The revanchist social and political desires of the dominant classes is as present as it has been over the last 500 years, and must be stopped without any hesitation.

2. Kristallnacht in Bolivia

by Maria Galindo (Nov 11, 2019) | leer en español aqui

I write in a torrential rain on a night that I have baptized as the Night of the Broken Crystals (Kristallnacht), because it’s aim is to sow fear, to open all the wounds of a racist, misogynist and homophobic colonial society. Revanchism has taken to the streets in search of blood, in search of enemies.

Today in Bolivia it is subversive to have hopes, the most subversive things are humor and disobedience, the most subversive choice is not to choose a side, and that is what we are betting on once again…

It tires me to have to repeat that the Movement to Socialism (MAS) is exporting to the world the idea that what is happening in Bolivia is a popular progressive bloc against an extreme and fundamentalist right. The government of Evo Morales was for many years responsible for dismantling of popular organizations by dividing them, corrupting them and imposing clientelist leadership, making pacts with the most conservative sectors of society including fundamentalist Christian sects to which he granted the fascist illegal candidacy of a Korean evangelical pastor, who was endorsed with the approval of the MAS.

At the same time Evo Morales was building himself up as the sole figurehead which has taken us as a country, and the MAS project itself, toward a dead end.

He has mistakenly converted himself into the sole figurehead, a symbol of the concentration of irreplaceable power. The figure bears the myth of the “Indigenous president” whose symbolic power is the color of his skin, which he carries with him, a government inhabited by a circle of corrupt of intellectuals and leaders who revere him because they need him as a mask, as Franz Fanon outlines in his book Black Skin, White Masks.

Evo is the figurehead and the mask, nothing more. All the populist content is merely rhetorical and that has led to the fact that today it is at the forefront of a political project that is exhausted and empty, and whose only possibility of continuity has been the destruction of all forms of dissent, criticism, debate, cultural or economic production. His model is neo-liberal consumerist, extractivist, ecocidal and clientelist…

I am convinced that the conflicts in Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Chile demonstrate, with different facets and under different contexts, the crisis of representative liberal democracy and the privatization of politics.

The entire neoliberal process has reduced the content of democracy to a bureaucratic act and election apparatus, and nothing more. This process has resulted in the elections having become legitimizing acts of the massive exclusion of the interests of society, of the interests of specific sectors, of the complex voices that make up a society in spectators legally excluded from the right to speak, think and decide. I call that the privatization of politics…

The crisis in Chile, Peru and Ecuador has different characteristics, but basically it expels society and social struggles outside of “politics” and takes us away from the idea that the solutions are “political,” deliberative and based on agreements. A generalized fascist turn and terror is installed to convert legitimate solutions and social questions into scenarios of violent counterposition of forces. That is what I call the fascist phase of neoliberalism…

That is why we are concentrating our efforts on simple discussions, not wasting energy in trying to convince any of the fascist sectors that build their respective stories, but affirming the social spaces that we have been opening for decades.

We take back the space of our own bodies. That is why the word democracy, which arouses hopes, can be summoned to preserve what we have, the place we occupy, and the freedoms that we do in fact exert without any permission.

3. What Happened in Bolivia? Was there a coup?

by Pablo Solón (Nov 11, 2019) | leer en español aqui

Evo Morales could have finished his third electoral mandate on the 22 January 2020 as a very popular president and the possibility of running for – and even winning – the 2024 elections, if he had not forced through his re-election for a fourth term. As the President of Bolivia, he a) did not recognise the 2016 referendum which voted NO to his re-election, b) pushed in 2017 for the Constitutional Tribunal to suspend the articles of the constitution that said that a person could only be re-elected one time, and c) committed fraud in the elections on 20 October to avoid a second round and to impose a party majority in parliament…

The government has treated the mobilisation as a fascist and racist coup. It is true that the sectors of the reactionary right have celebrated the protests. In Santa Cruz, the main leader of the Civic Committee, Luis Fernando Camacho, comes from an ultra-right organisation called the Union of Cruceño Youth. However, in other cities, there have been quite different articulations by independent groups with politicians from right and left leading the protests. In Potosí, the opposition to the government radicalised before the elections due to the signing of a 70 year contract without payment of royalties for the production of lithium hydroxide in the salt flats of Uyuni. In the case of La Paz, the National Committee for the Defense of Democracy counts among its main leaders two Ombudsman who served under the Evo Morales government and had denounced human rights violations such as the repression of the indigenous march of TIPNIS in 2011. For his part, Carlos Mesa, who was vice president during the neoliberal government of Sanchez de Lozada, and became the main electoral opponent of Evo Morales does not have a structured party base and was more a vehicle for opposition at the ballot box then a key organizer of the protests. The rebellion which Bolivia is experiencing is largely a spontaneous act led particularly by young people against the abuse of power…

It is important to be clear that there are indigenous peoples and workers on both the government and opposition side. The government clearly has more support in rural areas, but the opposition also includes coca producers from the Yungas, peasant leaders, mining workers, health and education workers, and above all young students, both middle and working class. Contrary to what happened in previous conflicts, it was the government that exacerbated the racism, saying that the protests were trying to take away the rural indigenous vote made in support of the government. During the conflict, there have been racist attacks from both sides.

4. After Morales Ousted in Coup, the Lithium Question Looms Large in Bolivia

by Vijay Prashad (Nov 12, 2019)

Over the past 13 years, Morales has tried to build a different relationship between his country and its resources. He has not wanted the resources to benefit the transnational mining firms, but rather to benefit his own population. Part of that promise was met as Bolivia’s poverty rate has declined, and as Bolivia’s population was able to improve its social indicators. Nationalization of resources combined with the use of its income to fund social development has played a role. The attitude of the Morales government toward the transnational firms produced a harsh response from them, many of them taking Bolivia to court.

Over the course of the past few years, Bolivia has struggled to raise investment to develop the lithium reserves in a way that brings the wealth back into the country for its people. Morales’ Vice President Álvaro García Linera had said that lithium is the “fuel that will feed the world.” Bolivia was unable to make deals with Western transnational firms; it decided to partner with Chinese firms. This made the Morales government vulnerable. It had walked into the new Cold War between the West and China. The coup against Morales cannot be understood without a glance at this clash.

When Evo Morales and the Movement for Socialism took power in 2006, the government immediately sought to undo decades of theft by transnational mining firms. Morales’ government seized several of the mining operations of the most powerful firms, such as Glencore, Jindal Steel & Power, Anglo-Argentine Pan American Energy, and South American Silver (now TriMetals Mining). It sent a message that business as usual was not going to continue…

The scale of these payouts [from lawsuits over nationalization] is enormous. It was estimated in 2014 that the public and private payments made for nationalization of these key sectors amounted to at least $1.9 billion (Bolivia’s GDP was at that time $28 billion)…

Bolivia’s key reserves are in lithium, which is essential for the electric car. Bolivia claims to have 70 percent of the world’s lithium reserves, mostly in the Salar de Uyuni salt flats. The complexity of the mining and processing has meant that Bolivia has not been able to develop the lithium industry on its own. It requires capital, and it requires expertise…

Chinese firms—such as TBEA Group and China Machinery Engineering—made a deal with YLB. It was being said that China’s Tianqi Lithium Group, which operates in Argentina, was going to make a deal with YLB. Both Chinese investment and the Bolivian lithium company were experimenting with new ways to both mine the lithium and to share the profits of the lithium. The idea that there might be a new social compact for the lithium was unacceptable to the main transnational mining companies.

Tesla (United States) and Pure Energy Minerals (Canada) both showed great interest in having a direct stake in Bolivian lithium. But they could not make a deal that would take into consideration the parameters set by the Morales government. Morales himself was a direct impediment to the takeover of the lithium fields by the non-Chinese transnational firms. He had to go.

After the coup, Tesla’s stock rose astronomically.

As a number of folks on the various listservs I’m on have noted, right now there are no simple answers, and what is going on in Bolivia (and surrouding parts of Latin America) are likely to have important repercussions that everyone should be watching very closely.