Theorizing the Anthropocene – part 3

This is part 3 in a three-part post reflecting on the Anthropocene and some of my dissertation research. You can read parts 1 and 2 here.

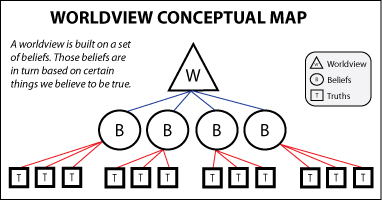

So this last post is trying to wrestle with the idea of the Anthropocene and questions of faith. In my original project that this is a part of, I was using the idea of faith as a way to try and get at the underlying truth claims of different political views in relation to the Anthropocene. But after having spent some more time thinking and writing and meditating on this question, it seems to me that perhaps faith is not quite the right way to frame the question I am trying to explore. In the process of trying to develop this idea further in response to some questions from my dissertation committee, I worked up the following conceptual map diagram, which is one way that I can imaging trying to think about this question that I am interested in exploring in my research.

Q: Is there a point where truth moves from faith to reality? From Fact to fiction? From fantasy to reality?

My final section moves to this question of faith and its relation to my work on the Anthropocene. Part of what I want to do in this project is to develop an argument about the Anthropocene as a new environmental worldview. I believe there are at least three, and maybe more, distinct environmental worldviews emerging in response to our changing world. These emerging worldviews center around a clash of truth claims about the basic foundation of our world.

On one hand we have the rise of Christian fundamentalism (especially Evangelical sects) and attacks on scientific truth claims that conflicts with certain literal interpretations of the Bible. These fundamentalist attacks are centered on several significant issues in both the earth and life sciences, principal among them evolution and the age of the earth. These beliefs are most often identified with young-earth, creationist and intelligent design politics. In addition, they often act as strong advocates for capitalist economic policies and minimal regulatory oversight for corporate business practices.

One such example is the Cornwall Alliance, an Evangelical, free market think tank which has produced an entire propaganda series called Resisting The Green Dragon, which attempts to paint environmental politics as a radical form of secular paganism that is anti-capitalist, anti-human and ultimately evil. Their political claims stem from a strictly literal reading of the Bible, especially the Old Testament, which they use as the foundation for their arguments about human dominion over the rest of the planet. These same arguments also serve to reinforce the claim that the earth is only 6,000 years old, that evolution as Darwin postulated it is not occurring, and that much of our worldview is distorted thanks to the rising influence of secular science that they believe contradicts Biblical teachings.

Another recent example, which I stumbled upon completely by accident, was from the September issue of Awake!, which is published by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and was being handed out in the subway in Queens. The cover and main articles were on doomsday, and the graphics perfectly captured nearly all of the themes I have been exploring here. This is the cover and inside art for this issue.

On the other hand we have the rise of various pagan, new age and ecotheological views which hold that the Earth is sacred and that we have a duty to care for and look after it. In the more traditional pagan circles this is usually framed in relation to the idea of the Goddess or Earth Mother which is the source of life in the world. In a more new-age or pantheistic framework this idea is often associated with the idea of Gaia, the spirit of the Earth. And in some Christian frameworks this is associated with green stewardship or ecospiritual movements which seek to make the Church a partner in environmentalism. In all of these movements the belief that the Earth and all life is sacred is in direct conflict with a literal Biblical reading which only affirms humans as unique and worthy of protection.

One such counterexample within the Evangelical movement is the Creation Care movement, which has sprung up in such places as the Evangelical Environmental Network (ENN), and argues for “creational responsibility” within the framework of Evangelical work. One powerful example of this logic can be found in Christopher Wright’s book The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative:

If the church awakens to the urgent need to address the ecological crisis and does so within its biblical framework of resources and vision, then it will engage in missional conflict with at least two other ideologies (and doubtless many more).

1. Destructive global capitalism and the greed that fuels it. There is no doubt that a major contributor to contemporary environmental damage is global capitalism’s insatiable demand for “more.” It is not only in the private sphere that the biblical truth is relevant that covetousness is idolatry and the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil, including this one. There is greed for

- minerals and oil, at any cost

- land to graze cattle for meat

- exotic animals and birds, to meet obscene human fashions in clothes, toys, ornaments, and aphrodisiacs

- commercial or tourist exploitation of fragile and irreplaceable habitats

- market domination through practices that produce the goods at least cost to the exploiter and maximum cost to the country and people exploited

For the church to get involved with issues of environmental protection it must be prepared to tackle the forces of greed and economic power, to confront vested interests and political machination, to recognize that more is at stake than just being kind to animals and nice to people. It must do the scientific research to make its case credible. It must be willing for the long, hard road that the struggle for justice and compassion in a fallen world demands in this as in all mission fields.

2. Pantheistic, neo-pagan and New Age spiritualities. Strangely, we may often find that people for whom such pantheistic, neo-pagan and New Age philosophies have great attraction are passionate about the natural order, but from a very different perspective. The church in its mission must bear witness to the great biblical claim that the earth is the Lord’s. The earth is not Gaia or Mother Earth. It is not a self-sustaining sentient being. It does not have independent potency. It is not to be worshiped, feared or even loved in a way that usurps the sole deity of the one living and personal Creator God. So our environmental mission is never romantic or mystical. We are not called to “union with nature” but to care for the earth as an act of love and obedience to the Creator and Redeemer. (pgs. 417-18)

Here we clearly see a distinct environmental worldview from that of the Biblical dominion arguments of young earth creationists who simultaneously defend free market capitalism, but also a rejection of the more pagan and pantheistic views which cross the line of acceptable Christian worldviews. So although the more fundamentalist wing of the Evangelical movement might not see eye-to-eye on some of the Creation Care issues, they are generally in agreement that they are both against any form of pagan or pantheistic environmentalism.

Although I am less interested in the pagan and pantheistic environmental views, as I believe focusing on them is less important in the context of conflicts over environmental protection and science, as most of these positions endorse both ecological protection and the basic scientific foundations of modern earth and life sciences, thus removing them from the direct confrontations we find with the Biblical fundamentalists. Where their views do matter are in areas like non-human politics and the boundaries of political communities and obligations, but this is something I hope to address more in the context of the Anthropocene as a new environmental framework in the earlier chapters (post-environmental and end of nature debates). Here my primary interest is the contestation over established earth and life science claims about the world from various ideological worldviews.

The third pole I see emerging in relation to these fundamentalist and ecotheological arguments is one grounded in an unshakable faith in capitalism, technology and progress to solve all of the world’s problems. Although this worldview of people advocating some version of this position are often secular, the unwavering faith of these arguments operates in a parallel fashion to the religious fundamentalism just examined. The existence of modern industrial civilization and free-market capitalism is taken as proof that this worldview is correct. This “proof” is self-legitimating in the same way that the Bible is claimed as a source of divine revelation and ultimate truth.

Here the larger claim I want to make is that the blind faith in progress and technology has come to operate in a similar manner as Biblical arguments in that they both reject the underlying environmental science claims, but they do this by drawing on different epistemological truth claims. For the religious claims, it is rooted in faith in the Bible. For the technology and progress claims, they are rooted in faith in modern industrial capitalism. And when these two views merge, as we see in arguments like those the Cornwall Alliance makes by hybridizing free market capitalism with Biblical dominion claims, the result is deadly dangerous. This is because the worldview being advocated no longer has any foundation in the real world, but draws almost entirely from ideological beliefs about the world which no longer require empirical validation or support. They are true simply because they say so.

When we reach such an moment, there is no longer any common ground for discussion or debate, and instead competing worldviews attempt to attack and destroy each other based on pure ideology. This becomes a recipe for both environmental inaction and public fissure, as we have already seen occur in the context of attacks on evolution curriculum in the schools and climate change agreements at the national or international level. The result, as Gross and Gilles argue in The Last Myth, is both a rise in apocalyptic thinking from secular and theological origins as well as decreased attention to the actual underlying issues (population, resource availability, sustainability, etc).

We no longer debate the actual issues, but instead the proper interpretive frame for discussing those issues. Once we get stuck in this meta-level debate there is no resolution because there is no longer any truth but only matters of faith. I believe capitalism is the best system ever designed. I believe technology will solve global warming. I believe the Rapture is coming soon. I believe the earth is only 6,000 years old. Faith, not fact, is king. How we wrestle with this reality as it impacts environmental politics in relation to this this emerging idea of the Anthropocene is what I ultimately want this part of the project to attempt to grapple with, and is how I am trying to approach the idea of faith in relation to the Anthropocene.

This is all a work in progress, and my thinking on this is still developing and taking shape. If you have thoughts on any of this, please leave a comment below or drop me a note here.

Until next time…think deep.

###