Hurricane Sandy: The New Normal Revisited

{Revised 11/4} *Added more discussion on the energy policy-natural disasters link – thanks to BL-T.

Roger Pielke recently wrote a piece in the WSJ called ‘Hurricanes and Human Choice’ that discussed the relationship between increasing natural disaster impacts and human settlement and lifestyle choices. In that piece he argued against considering Hurricane Sandy as some sort of “new normal” event, a claim which I explored and largely supported in my last post here. Two points made by Pielke are worth meditating on:

#1) But to call Sandy a harbinger of a “new normal,” in which unprecedented weather events cause unprecedented destruction, would be wrong. This historic storm should remind us that planet Earth is a dangerous place, where extreme events are commonplace and disasters are to be expected. In the proper context, Sandy is less an example of how bad things can get than a reminder that they could be much worse.

#2) Another danger: Public discussion of disasters risks being taken over by the climate lobby and its allies, who exploit every extreme event to argue for action on energy policy. In New York this week, Gov. Andrew Cuomo declared: “I think at this point it is undeniable but that we have a higher frequency of these extreme weather situations and we’re going to have to deal with it.” New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg spoke similarly.“

While I think Pielke offers some valid points about some of the historical trends, I disagree with the larger claim he makes that recent natural disasters are not that bad by historical comparison, and are essentially being over-hyped and cherry-picked for political reasons (Look for a future post on this question of historical risk). Because of his own bias on this point he fails to see the bigger historical picture here, which is precisely what the “new normal” argument is about.

Consider the following remark made by Pielke:

Humans do affect the climate system, and it is indeed important to take action on energy policy—but to connect energy policy and disasters makes little scientific or policy sense.

If we break the internal logic of this claim apart, it would go something like the following:

- Humans affect climate systems

- Energy policy matters and needs attention

- There is no connection between our choice of energy and the impacts of disasters

While many people would agree with the first two points, the last one should be deeply troubling to many people because it requires some amazing denial acrobatics to maintain such a claim. Think about it this way. What were some of the biggest impacts from recent natural disasters in the US? Here’s my short list.

- Direct loss of life

- Damaged/Destroyed property (public and private)

- Crippled infrastructure

- Collapse of essential services and disruption of secondary services

- Economic/Job losses

{*Update}So how do these connect energy policy to natural disasters, and why do I think Pielke is wrong and performing “some amazing denial acrobatics?” I would argue there are several ways.

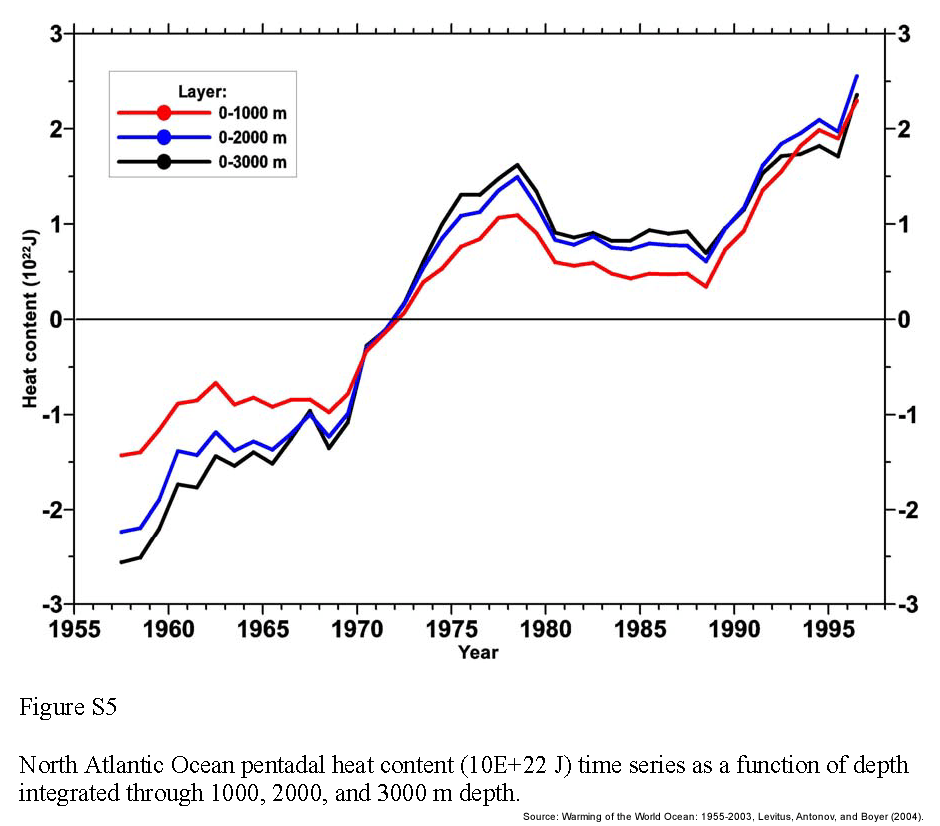

1 We know for a fact that tropical hurricanes coming in from the Atlantic are shaped by both atmospheric and oceanic temperatures. We also know that warmer waters tends to produce stronger storms. A 2005 study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters by Levitus, Antonov, and Boyer called “Warming of the World Ocean: 1955-2003” documented this historical trend over the last half century. The authors found increased ocean heat content across the board (Figure 5), with the most dramatic increases being in the three Atlantic regions (Figure 2).

In discussing the cause of this ocean heat content increase the authors point to fossil fuel driven global warming as the leading cause, while acknowledging some of the limitations that global ocean temperature data imposes.

In terms of the causes of the increase in ocean heat content we believe that the long-term trend as seen in these records is due to the increase of greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere [Levitus et al., 2001]. In fact, estimates of the net radiative forcing of the Earth system [Hansen et al., 1997] suggest the possibility that we may be underestimating ocean warming. This is possible since we do not have complete data coverage for the world ocean. However, the large decrease in ocean heat content starting around 1980 suggests that internal variability of the Earth system significantly affects Earth’s heat balance on decadal time-scales.

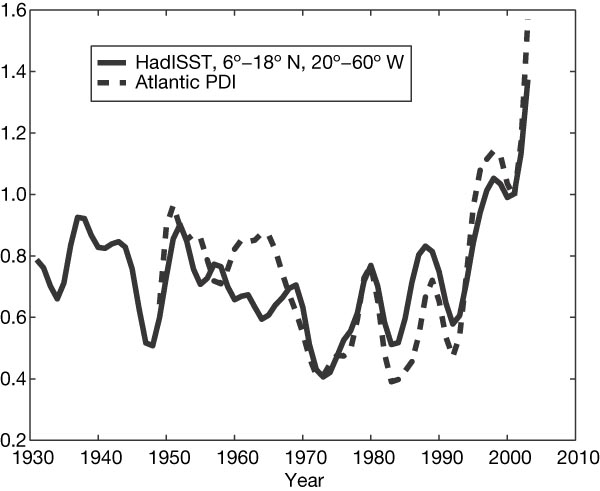

A year later James Elsner of Florida State University published one of the first studies showing a statistical correlation between Atlantic sea surface temperatures (SST), increasing tropical cyclone activity and climate change. The article, ‘Evidence in support of the climate change–Atlantic hurricane hypothesis,’ was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters in 2006.

The power of Atlantic tropical cyclones is rising rather dramatically and the increase is correlated with an increase in the late summer/early fall sea surface temperature over the North Atlantic. A debate concerns the nature of these increases with some studies attributing them to a natural climate fluctuation, known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), and others suggesting climate change related to anthropogenic increases in radiative forcing from greenhouse-gases. Here tests for causality using the global mean near-surface air temperature (GT) and Atlantic sea surface temperature (SST) records during the Atlantic hurricane season are applied…Elsner showed that GT is useful in predicting Atlantic SST. SST, however, is not useful in predicting GT. Thus GT “causes” SST, supporting the hypothesis that climate change influences hurricane intensity.

Additional evidence for these claims was provided by Webster et al. in a 2006 report called ‘Changes in Tropical Cyclone Number, Duration, and Intensity in a Warming Environment‘ and published in the journal Science. This study showed that although average tropical cyclone events had not increased between 1970 and 2004, what had changed was the strength of these storms, especially of Category 4 or 5 hurricanes. Here they found a 50% increase in frequency starting in the later half of their study period (~1987 onward).

We conclude that global data indicate a 30-year trend toward more frequent and intense hurricanes, corroborated by the results of the recent regional assessment. This trend is not inconsistent with recent climate model simulations that a doubling of CO2 may increase the frequency of the most intense cyclones, although attribution of the 30-year trends to global warming would require a longer global data record and, especially, a deeper understanding of the role of hurricanes in the general circulation of the atmosphere and ocean, even in the present climate state.

The recent regional assessment mentioned above by Emanuel also looked at some of these dynamics, but in particular at something called the power dissipation index or PDI (For those interested, PDI is technically the “sum of the maximum one-minute sustained wind speed cubed, at six-hourly intervals, for all periods when the cyclone is at least tropical storm strength”). Emanuel found a significant increase in the Atlantic region PDI over the past 30 years, as cited by Webster et al. in the article above. Here’s the most important of the charts from Emanuel’s paper for our interests here, where the spike in PDI since 1990 is clearly evident.

And here is Emanuel’s discussion on the data underlying this chart.

I define an index of the potential destructiveness of hurricanes based on the total dissipation of power, integrated over the lifetime of the cyclone [the PDI], and show that this index has increased markedly since the mid-1970s. This trend is due to both longer storm lifetimes and greater storm intensities. I find that the record of net hurricane power dissipation is highly correlated with tropical sea surface temperature, reflecting well-documented climate signals, including multi-decadal oscillations in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, and global warming. My results suggest that future warming may lead to an upward trend in tropical cyclone destructive potential, and—taking into account an increasing coastal population—a substantial increase in hurricane-related losses in the twenty-first century…the large upswing in the last decade is unprecedented, and probably reflects the effect of global warming…the near doubling of power dissipation over the period of record should be a matter of some concern, as it is a measure of the destructive potential of tropical cyclones. Moreover, if upper ocean mixing by tropical cyclones is an important contributor to the thermohaline circulation, as hypothesized by the author, then global warming should result in an increase in the circulation and therefore an increase in oceanic enthalpy transport from the tropics to higher latitudes.

That last part is pretty technical in its lingo, but basically Emanuel is saying that the movement of ocean waters (influenced by density, fresh-v-salt content, temperature and other factors) may be noticeably impacted by larger, more powerful hurricanes (as measured by the PDI), which will in turn carry that tropical storm energy from the Caribbean up to the Atlantic Coast, at least in the case of hurricanes in our region. To get a sense of how these flows work, take a look at this animation of how Thermohaline Circulation works.

And finally, a report published by Goldenberg et al. in Science over a decade ago (2001) titled ‘The Recent Increase in Atlantic Hurricane Activity: Causes and Implications‘ found similar trends already in that period, before Katrina, Sandy or any of the other larger post 2000 weather events. Discussing their findings they wrote:

The years 1995 to 2000 experienced the highest level of North Atlantic hurricane activity in the reliable record. Compared with the generally low activity of the previous 24 years (1971 to 1994), the past 6 years have seen a doubling of overall activity for the whole basin, a 2.5-fold increase in major hurricanes (≥50 meters per second), and a fivefold increase in hurricanes affecting the Caribbean. The greater activity results from simultaneous increases in North Atlantic sea-surface temperatures and decreases in vertical wind shear. Because these changes exhibit a multidecadal time scale, the present high level of hurricane activity is likely to persist for an additional ∼10 to 40 years.

Add to all that the fact that we just saw record high temperatures in the NE, both on land in at sea, for the last 4 months and you have the recipe for a perfect storm. What all of these studies suggest is that there is a correlation between increasingly destructive storms, increasing ocean temperatures, increasing sea surface temperatures and a warming planet. Finally, there is now a large body of science which has firmly established a link between global warming and increasing CO2 levels, especially from the burning of fossil fuels. Therefore to suggest, as Pielke does, that we cannot connect Hurricane Sandy to American energy policy suggests to me that he believes we cannot connect global warming to our energy policy, which is precisely why I called his larger argument “some amazing denial acrobatics.”

I agree that we cannot say with 100% certainty that Sandy was a direct result of global warming. That’s a claim we will never be able to make, because the climate system is too dynamic and complex to make single-cause arguments. But we can say with increasing scientific certainty that nearly all of the individual factors going into creating more dynamic, and therefore more destructive tropical weather events, are increasing, as I have tried to show with a few of the many studies on this topic. The important point is that most of the major indicators suggest that these storms are growing in intensity and are increasingly being linked to climate change in general, and global warming in particular, both of which are a direct result of our energy policies and choices!

{*end update}

In the immediate NY context, think about what we have seen this week.

- 150+ estimated deaths

- Thousands of homes decimated, plus innumerable businesses and gov’t offices damaged

- Subways, Trains, Tunnels and Bridges all closed, many for over a week

- Hospitals evacuated, widespread power outages, phone services disruptions, gas and water disrupted

- $50 billion in direct damage estimates, plus $20 billion in estimated insurance costs

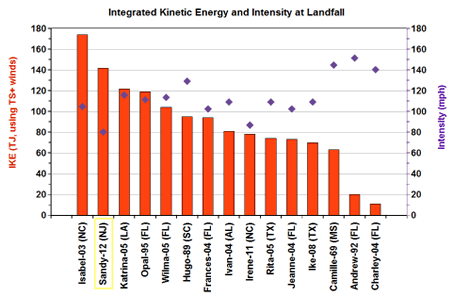

All of this took place because we had a minor Category 1 hurricane! That’s important to emphasize. This was not even a serious category 2 hurricane by the time it made landfall near New York. Knowing that, consider the following discussion about storm modelling which was going on here in NYC.

Cynthia Rosenzweig and Vivien Gornitz are scientists on a team at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) and Columbia University, New York City, investigating future climate change impacts in the metropolitan area. Gornitz and other NASA scientists have been working with the New York City Department (DEP) of Environmental Protection since 2004, by using computer models to simulate future climates and sea level rise. Recently, computer modeling studies have provided a more detailed picture of sea level rise around New York by the 2050s.

“With sea level at these higher levels, flooding by major storms would inundate many low-lying neighborhoods and shut down the entire metropolitan transportation system with much greater frequency,” said Gornitz.

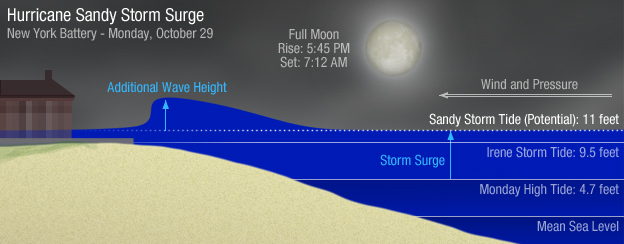

With sea level rise, New York City faces an increased risk of hurricane storm surge. Storm surge is an above normal rise in sea level accompanying a hurricane. Wind speed is the determining factor in the scale, as storm surge values are highly dependent on the slope of the continental shelf and the shape of the coastline, in the landfall region.

This quote is from an October 26th NASA report about rising sea levels and New York City. October 26, 2006! That’s right, the research news bulletin was published by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies nearly a decade ago, and was titled ‘NASA Looks at Sea Level Rise, Hurricane Risks to New York City.’ Chris Mooney, authors of the 2007 book Storm World: Hurricanes, Politics, and the Battle Over Global Warming, has also written about this recently, pointing out just how prescient the Goddard Institute predictions turned out to be.

Scientists at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York have been studying that city’s vulnerability to hurricane impacts in a changing world, and calculated that with 1.5 feet of sea level rise, a worst-case-scenario Category 3 hurricane could submerge “the Rockaways, Coney Island, much of southern Brooklyn and Queens, portions of Long Island City, Astoria, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens, lower Manhattan, and eastern Staten Island from Great Kills Harbor north to the Verrazano Bridge.”

This was a projection made in 2006, but it almost perfectly describes what just happened this past week. And this is precisely why the point Mooney makes about the link between politics and the issues we are debating (or not debating, like energy policy and climate change risks) have such a huge impact on our daily lives, especially if we live in the path of these natural disasters. The fact that scientists here in New York were essentially describing exactly what happened, based on models and the latest research, yet nothing was done, should be a wake up call to a much larger and more systemic problem that impacts us all, coastal residents or not.

The point is that we have a terrible track record of dealing with long-range risks in this country. This is exacerbated by a presentist, science-phobic mindset on full display in the saga of 2012 presidential debates — which now, in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, looks utterly inane. The debates completely ignored climate change — and then much of Manhattan was flooded. So do we really think that Jim Lehrer, Candy Crowley, and Bob Schieffer are the sort of journalists that ought to be steering conversations between our presidential candidates?

But what is most troubling is that Hurricane Sandy wasn’t a category 3 hurricane as measured in the Saffir-Simpson scale (1-5). As I mentioned already, it wasn’t even a Category 2. It was at the low end of a Category 1 storm and dropping, although you’d never know it being here in New York. But what Sandy lacked in wind speed it made up for in something known as integrated kinetic energy, or IKE, and its “frankenstorm” size. Add to that the fact that Sandy also made landfall in almost perfect sync with the moon and high tide, plus the arctic cold pushing down from the Northwest, and you literally had the perfect storm setup in the works. Here’s a useful illustration of why the storm surge plus the tide matters in this case.

Check out this chart from an article in today’s WSJ by Brian McNoldy on the weather science behind the storm. I’d also suggest checking out this very informative article from 2005 by the Goddard Institute layout out some of the important links between climate change and risks specific to New York City.

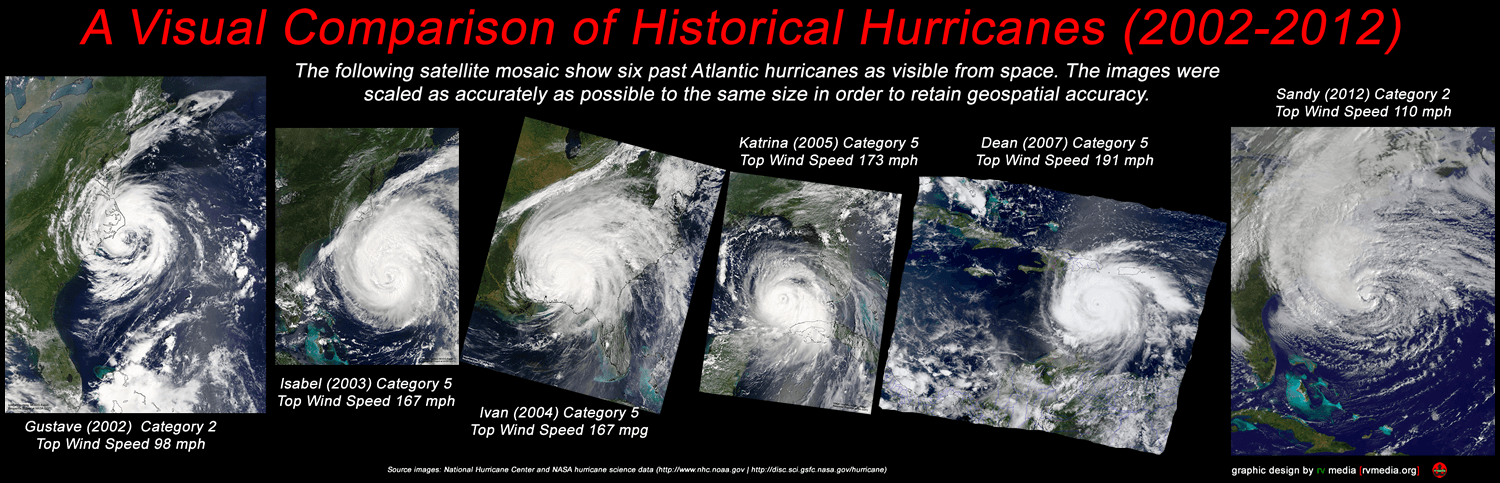

Those purple diamonds are the wind speed used in the Category reference above, and as you can see, Sandy is much lower in the intensity than its total IKE, and by a significant amount. Another way to think about this is to look at the actual size of these storms. To help with that, I put together a quick graphical comparison of some of the larger hurricanes over the last decade.

And this is precisely why the point Mooney makes about the link between politics and the issues we are debating (or not debating, like energy policy and climate change risks) have a huge impact on our daily lives, especially if we live in the path of these natural disasters.

The point is that we have a terrible track record of dealing with long-range risks in this country. This is exacerbated by a presentist, science-phobic mindset on full display in the saga of 2012 presidential debates — which now, in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, looks utterly inane. The debates completely ignored climate change — and then much of Manhattan was flooded. So do we really think that Jim Lehrer, Candy Crowley, and Bob Schieffer are the sort of journalists that ought to be steering conversations between our presidential candidates?

And this is the real take away point that is part of the larger story. To claim, as Pielke does, that there is no relationship between our energy policy and natural disasters is to claim that there is no connection between our energy policy and climate change, which amounts to arguing that climate change is not a product of the lifestyle and energy choices of the leading industrial nations in the world. And to claim that these leading industrial nations energy choices don’t have an impact on climate change, and global warming in specific, is like saying that the IPCC is not real science because the believe there is a correlation between human activities and climate change. Last time I checked, that was still the international consensus, even if “the projections of global climate models should be regarded as educated guesses.”

Not talking about the link between energy policy and the inevitable boomerang climate blowback is a dangerous form of climate change denial, especially when it is dressed up as supposed concern about climate change. Until we are willing to acknowledge that our cheap energy, fossil fuel glut has caught up to us, and is only going to get better, we might as well all be alcoholics toasting out sobriety at an AAA meeting, because that about how much sense it makes to delink energy policy from climate change and growing ecological and cultural risk. You can’t, as hurricane Sandy brutally reminded us when she killed people and power infrastructure alike.

Until next time…now’s a great time to brush up on your candle making skills.

###

black people aren’t the only ppl reneivicg food stamps There are plenty of white people on welfare as well as other races It’s a shame that some ppl do abuse the system But alot of ppl are on welfare to get on their feet Alot of black ppl weren’t awarded some of the benefits that white ppl were, although we all choose our own path It is still much harder for blacks in America today as it was in the 50,s nd 60 s U are only white maybe in this world that matters but